Religion and Music in England at the Turn of the Twentieth Century

by Leon Botstein

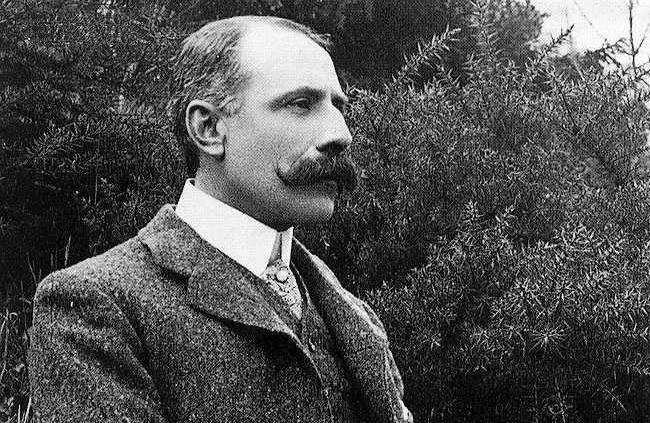

Edward Elgar’s two monumental masterpieces for chorus and orchestra, The Dream of Gerontius and The Apostles, mirror the tensions and contradictions that surrounded religion at the end of the Victorian era.

Elgar, a Catholic, had experienced isolation and prejudice, particularly in his younger years. But he also witnessed a Catholic revival in England, the rise to prominence of John Henry Cardinal Newman as an influential English voice (Newman was the author of the poem that became the text of Gerontius), and the lessening of anti-Catholic sentiment. The Catholic revival and the resurgence of Anglo-Catholic High Church Anglicanism were in part a reaction against a long standing perception of the Anglican faith as spiritually deficient—a sentiment that came into broad public view already in the 1830s.

Adherence to the Church of England appeared to require none of the terrifying internal discipline required of Protestant sects descended from Calvin—evident even in idiosyncratic nineteenth century incarnations such as Seventh Day Adventists. The Lutheran idea of faith alone and the direct connection between the individual and the divine were tempered. The Anglican faith could easily be seen as an unstable and unsatisfactory compromise. It retained the principle of apostolic succession, the indelibility of ordination, and the centrality of communion—replete in some covert Anglican circles with a residual belief in the miracle of transubstantiation. But yet Anglicanism seemed to lack the mystery and authentic aura of Catholicism, in which the church as an institution and community embodied directly the spirit of Christ, and in which the individual was not abandoned to face God alone, but suffered through life until death as part of a sacred community.

But the Church of England was the official church of the nation with the sovereign at its head. That only underscored the national significance of Anglicanism and its support of British imperial ambitions, which were at their height when Elgar composed The Apostles. Elgar may have been a Catholic but he was a patriot and enthusiast of imperialism first. His choral works were written for the great Anglican choral tradition of amateur choral festivals—a central part of English cultural life in the 19th century and the cause for so much great choral repertoire, from Mendelssohn and Dvořák on. It is therefore not surprising that in both Gerontius and The Apostles an unmistakable triumphalist quasi-imperial grandeur (perhaps suggestive of a national conceit of superiority) is audible, which is perhaps why Elgar’s great choral music has travelled so poorly outside of the British Isles.

At the same time, Elgar’s generation—and indeed Elgar himself—were witness to the overwhelming rise in anti-religious sentiment, particularly among the educated elite of Europe and America. Secularism and skepticism were in the ascendency, fueled by the progress of rationality evident in science and technology. Mendel, Darwin, and Maxwell had revealed the mysteries of nature. The urban landscape, weaponry, transport, and even the modes of musical transmission, all had been transformed by new gadgets and devices, each reflective of the progress of science and reason. A retreat into mysticism and miracles seemed unnecessary. If one adds to this the allure of socialism and communism—utopian ideologies based on reason designed to rid humanity of poverty and inequality—it becomes clear why religion, particularly the Anglican Church and Catholicism, was on the defensive as a superstitious remnant of a pre-democratic and even feudal age.

In an age when the material and rational were triumphant, the aesthetic—art—more and more began to satisfy the need for a quasi-religious experience that was not reducible to cold, utilitarian calculation. Art offered an alternative to the ethos of efficiency and sufficient explanation by evidence and argument. In Elgar’s generation it was Wagner that best exemplified the elevation of art into the status of a modern religion. And there is, in The Apostles, the audible influence of the master of Bayreuth, a temple to art, in which a nasty self-indulgent genius was deified.

This context helps explain why Elgar struggled so much with this project. It explains why he chose to write his own text, which allowed him to foreground the humanity of two characters—Mary Magdalene and Judas—and render them sympathetic. In contrast to Bach’s Passions, The Apostles is quite democratic and down to earth, a retelling, designed for mass amateur choral participation as well as mass listening, of a divine mystery. The awe at the mystery of Christ is the Catholic aspect of the work, but the notion that the key servants of Christ were just ordinary, well-intentioned but unremarkable human beings reveals how attuned Elgar was to his ultimately resolutely Protestant and, with regard to religion, increasingly skeptical public.