Elgar’s The Apostles

by Byron Adams

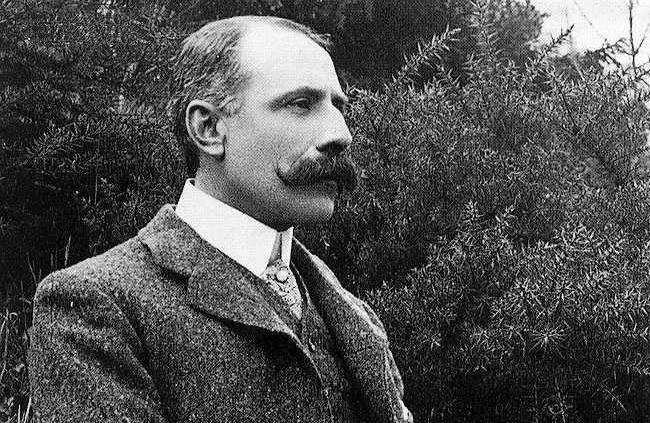

In the usual narrative of Edward Elgar’s career, the composer sprang overnight from provincial obscurity to international fame with the 1899 premiere of his Variations on an Original Theme, Op. 36, now known as the Enigma Variations. Unsurprisingly, the truth is more complicated: Elgar was already becoming well known through a series of acclaimed choral works, such as The Black Knight, Op. 25 (1892), Scenes from the Saga of King Olaf, Op. 30 (1896), and Caractacus, Op. 35 (1898). All of these scores were successful at their first performances, and British choral societies took them up rapidly. Singers delighted in the challenges posed by these scores; both audiences and critics relished Elgar’s brilliant orchestration.

Despite its inadequate rehearsed premiere at the 1900 Birmingham Festival, Elgar’s oratorio The Dream of Gerontius, Op. 38, assumed an honored place in the British choral repertory by the autumn of 1902, thanks to a carefully prepared German performance at Dusseldorf in May of that year. Even before this important performance of The Dream of Gerontius, the Birmingham Festival had commissioned an extended choral work on a sacred theme from Elgar for their 1903 festival. Elgar proposed as his subject the calling of the apostles. This idea had engaged him since his childhood when a schoolmaster had characterized the apostles as “poor men, young men, at the time of their calling; perhaps before the descent of the Holy Ghost not cleverer than some of you here.”

Elgar conceived a grandiose design of which The Apostles would be just the first part: a trilogy of oratorios that would span the calling of the Apostles through the founding of the Early Church and conclude with the Last Judgment. The ambitious scope of this project clearly emulated Wagner’s Der Ring des Nibelungen. Elgar made a pilgrimage to Bayreuth in 1902 seeking inspiration for The Apostles. There he heard the first three music dramas of Der Ring as well as Parsifal, the music of which would exert a discernable influence upon The Apostles. On July 2, 1902, Elgar wrote exuberantly to a friend, “I am now plotting GIGANTIC WORK.”

Elgar decided to follow Wagner’s example and create his own text for the trilogy. Lacking Wagner’s literary expertise, however, he wisely chose to construct his libretto from selected biblical passages. After choosing episodes from the Gospels, Elgar filled in this frame with various Scriptural verses, sometimes wrenching lines from their original context for his own purposes. Unfortunately, he miscalculated the time that it would take to complete such a massive project. Facing deadlines from the Birmingham Festival, Elgar severely truncated his original plan. In the end, only two oratorios of the projected three were completed: The Apostles and its relatively concise successor, The Kingdom. (The final oratorio, provisionally titled The Last Judgment, was never written; Elgar made only a few jottings for it.)

In The Apostles, Elgar places less emphasis on the sufferings of Christ than on the experiences of His followers. Elgar lavished special attention on the two outcasts, Mary Magdalene and Judas. Both characters are assigned extended scenes during which they express their shame and guilt. The Pre-Raphaelite luxuriousness of Mary Magdalene’s music repelled some high-minded critics. E.A. Baughan, for example, carped that the “repentance of Mary Magdalene, which really has nothing to do with the Apostles . . . is an unessential detail.” Elgar’s compassionate treatment of Judas seemed equally puzzling. Elgar was prone to periods of depression and he clearly particularly identified with Judas to some degree. During the composition of The Apostles, he wrote to a friend: “To my mind, Judas’ crime or sin was despair; not only the betrayal, which was done for a worldly purpose.”

The premiere of The Apostles in Birmingham on October 14, 1903, was greeted with acclaim, despite critical reservations about the flamboyance of the orchestration. In spite of the success of The Apostles, Elgar’s enthusiasm for his Wagnerian project had begun to wane by the time he began to compose the second oratorio, The Kingdom. In addition, his excursions into biblical exegesis had caused his Christian faith to waver and his inspiration to falter. For whatever reason, Elgar’s “gigantic work” was destined to remain a vast torso forever incomplete.

Byron Adams is a Professor of Musicology at the University of California, Riverside.