Intolerance

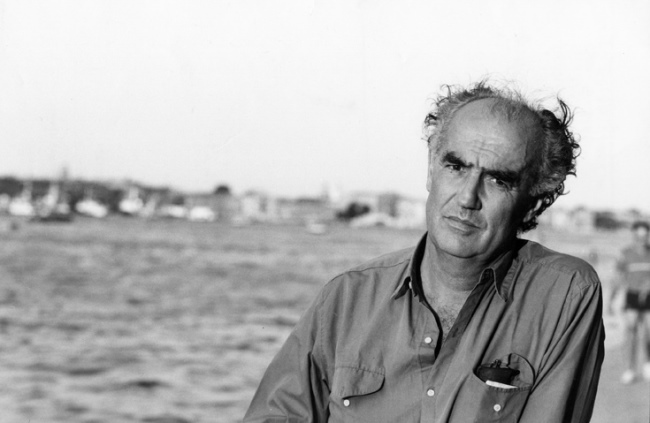

By Leon Botstein

It would be hard to imagine a work more pertinent to our times than Luigi Nono’s Intolleranza 1960. It is a work of musical theater that tells the story of an emigrant worker who encounters prejudice, injustice, incarceration, and violence. It assumes a political context in Europe of the threat of a return to fascism. Intolleranza 1960 suggests that none of us can afford to assume that we are immune to the character of the public life we not only live in, but passively and actively helped create.

Whatever one’s politics may be, there is no question that the tolerance of immigrants, the subject of Intolleranza 1960, is declining in the present day, and the distinctions we make between ourselves and “others,” the basis of anti-immigrant sentiment, is on the rise both in Europe and the United States. We are also witnesses to the steady rise of illiberalism in politics, an appetite for violence, and a populist embrace of autocracy. We seem content with a growing inequality of wealth and are reluctant to address the economic and social realities that have emerged since 1960, particularly as a consequence of new technologies and that overused and poorly understood term, globalization.

What distinguishes 1960 from 2018 is that in 1960 the central element in politics was the critique of capitalism. That is not the case now. We no longer accept the idea that socialism and communism might challenge the unrestrained embrace of the market and private property. The contrast between “left” and “right” in 1960 still derived from World War II and the experience of fascism in Italy, Germany, and Spain. Members of Luigi Nono’s generation believed in the possibility, if not the necessity, of radical political change. Rightly or wrongly, they were in part inspired by countries behind the Iron Curtain. Stalinism seemed in retreat (despite the suppression of the Hungarian Revolution in 1956). In the post-world war West, two contradictory sentiments prevailed: the belief in Communism as a viable alternative, and the fear of it as an ominous evil threat from Eastern Europe. Both of these beliefs strengthened the case in the West for the welfare state and social democracy. In America, the New Deal remained until the late 1960s, a glorious example of how fairness and justice—the realization of Roosevelt’s four freedoms of speech and of religion, and from fear and want—might be possible within the framework of democracy.

When Nono wrote Intolleranza 1960 the trauma of fascism and the World War had not become a faded memory. The two questions—why the catastrophe that had come to an end in 1945 had happened in the first place, and how a repeat of that disaster could be averted—were the central preoccupations of the composers, artists, and writers who rose to prominence in the 15 years between the end of the war and 1960. As result, it seemed implausible to simply continue aesthetic traditions that had flourished before the 1930s. If the making of art still had relevance, it needed to work against continuity, tradition, and complacency. Art needed to be unsettling and not merely affirmative of the status quo. It needed to challenge traditional notions of beauty. It had to be adequate to the dangers of contemporary life and confront the contradictions, absurdities, and brutality of the historical moment, including the threat of nuclear war that marked the Cold War. It is no surprise then that 1960 was a high water mark of 20th-century modernism in the arts. Nono’s score seeks to be resolutely new and defiant of conventional expectations. It still evokes the mix of enthusiasm and shock that accompanied its first performances. It celebrates the departures from late Romanticism and Neo-classicism in sound and form pioneered by modernism.

A singular irony of Nono’s modernism is that during the Cold War, radical innovations in music composition were celebrated in the West as markers of a free society. Despite Nono’s overt political intent, his manner of music making was in stark contrast to the kind of music supported by the Soviet state and dominant throughout Eastern Europe. That music (Shostakovich, for example) was viewed in the West as regressive and conservative, even though it was thought to be populist and acceptable by Communist ideology. The irony was clear. Nono was using his freedom to make a case with music that never quite gained a wide following, whereas in the presumably progressive albeit autocratic socialist state, a regressive conservative music was cherished by the public. Progressive politics in the West was briefly tied to an innovative and radical aesthetic. Its credibility was enhanced by the idea that Nono’s modernism was evidence of the power and potential of the freedom of the individual, to whose protection the West was committed.

Nono has much to say to us in Intolleranza 1960, because we live in a time when his synthesis of radical politics and aesthetics is very pertinent. 1989 and the end of the Cold War did not usher in a new golden age of democracy, freedom, and justice. The challenges we face once again suggest that art needs to be more than a decorative enterprise. It must possess an ethical and political dimension, as well as an obligation to speak independently and truthfully. In 1960 Nono understood how to electrify and shock the concert and opera audience; the continuities with 19th-century practices had not been entirely broken. In 2018 those continuities no longer dominate, and the entire enterprise of concert and operatic music carries less significance. Furthermore, Nono’s musical modernism is, at best, in retreat. It retains whatever currency it has mostly as a noble fragment of the past. Nevertheless it is an intense, innovative, and passionate experiment in sonority that pervades the listener’s consciousness. It is a reminder that for Nono, art and music mattered, that literature and philosophy needed to inform the making of music and help shape music so that it might challenge the public to address injustice and inhumanity. These beliefs need to be cherished and emulated. Intolleranza 1960 is a unique masterpiece that can inspire music and theatre in our own times. Its startling relevance today justifies Nono’s faith in the ethical power of the aesthetic imagination.